How the virus is changing people and our planet?

This Earth Day, ACT FOR YOUR PLANET highlights 10 ways that the virus is affecting our planet, for better and for worse. No single event of the last 50 years has had a bigger impact on our world than the ongoing coronavirus pandemic

No single event of the last 50 years has had a bigger impact on our world than the ongoing coronavirus pandemic

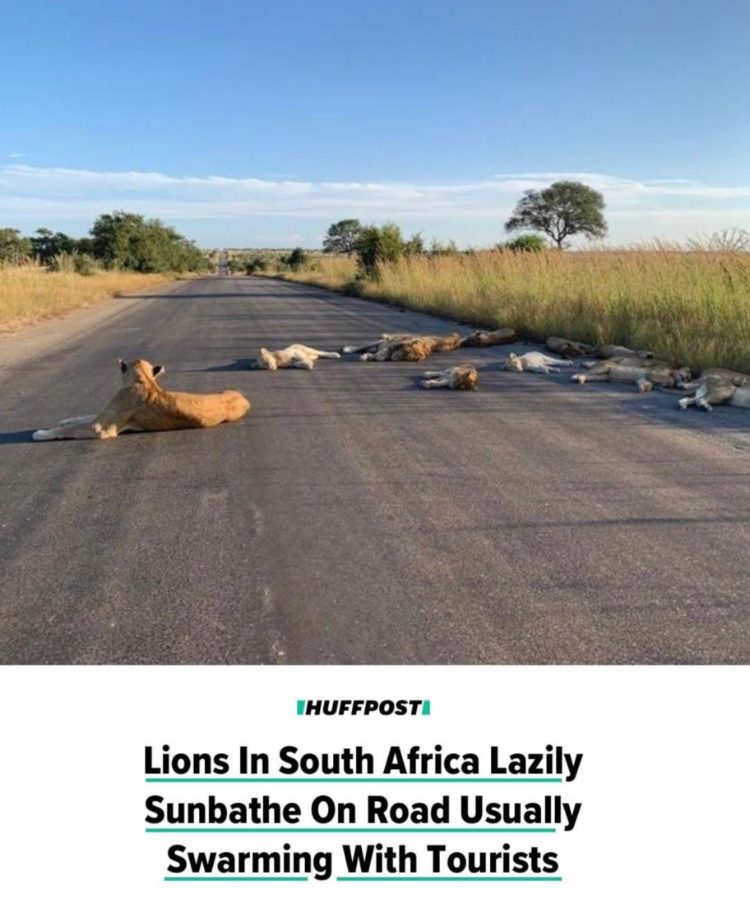

- Wildlife is reclaiming lost territory

Tales of dolphins and swans returning to the canals of Venice and elephants sauntering through a village in Yunnan, China turned out to be fake news as people clamoured for positive stories amid the terrifying Covid-19 media blizzard in March. But the return of animals to places where humans have retreated is really happening

- Water-scarce places reveal their vulnerability

We are being advised by health authorities to wash our hands more frequently for at least 20 seconds to prevent outbreaks. But what about countries like Pakistan and India, where clean water is in short supply? Some 40 per cent of the world’s population lacks access to basic hand-washing facilities at home, and one billion people live in informal settlements, where overcrowding and lack of water access can fuel the spread of diseases like Covid-19. While aid agencies are helping water-stressed countries by installing portable hand-washing stations in public areas and other temporary measures, the pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for better water management to cope with future crises.

- A stick in the wheel of the circular economy

Face masks are ending up in the ocean.

Consumption has been hit hard by coronavirus. But in certain categories, such as groceries and personal hygiene, spending has grown as locked-down consumers opt for online deliveries. the low cost of oil has pushed up the price of recycled plastic, putting many recyclers out of business and threatening to derail corporate sustainable packaging commitments.This has led to concerns that coronavirus has brought with it an increase in plastic pollution, as beaches and waterways become clogged with discarded disposable face masks. Plastic bags are also making a comeback as retailers rescind single-use bag bans and scrap bring-your-own-container schemes in fear they’ll help spread the disease. The revival of single-use plastic has been prompted by research from plastic industry-backed groups that claims the virus can survive on plastic for longer than on other surfaces

- The viral threat of losing forests

Clearing forests is likely to increase the occurrence of diseases like Covid-19, as animals come into closer contact with people. In Indonesia, home to some of the world’s largest expanses of rainforest, some 8,000 hectares of forest have been lost so far this year.

- Will personal freedom restrictions linger?

Not since World War II have governments taken such radical policy measures to curb the personal freedoms of their citizens. In locked-down China, public transport was stopped and drones deployed to police the mandatory wearing of face masks. In Dubai, citizens could not leave their homes at all, and were only permitted to go to a supermarket after booking an appointment through a government website. In Singapore, citizens are being encouraged to ‘snitch’ on one another to the authorities if they witness safe distancing violations. Human rights watchers worry that some of these measures could remain in place after lockdowns are lifted. Contract tracing apps are a particular cause for concern. These apps pose an “unprecedented” level of surveillance on citizens

- Racial discrimination is rising

Ever since the virus emerged from Wuhan, reports of racial discrimination against people of Chinese descent have been documented around the world, from Egypt to England. In Hong Kong, racial incidents have been reported against mainland Chinese and, in China, against people from Hubei, the province of which Wuhan is the capital. The World Health Organisation recommended that the virus be known as Covid-19 to avoid the disease being associated with its country of origin.

- Agriculture is going local

Population control measures have disrupted food transport links, worries over food shortages have been followed by vast volumes of unsold produce, andfarm labour has been in short supply in many countries, highlighting the value in local agriculture. Nowhere has this been demonstrated like China, the first country to be hit by the virus. Aided by e-commerce giants Alibaba and JD.com, consumer demand has been matched with farmer supply, closing the gap between urban markets and the growing regions, providing lessons for other countries in more resilient, sustainable food supply chains of the future

- Poverty exacerbated, inequality widening

It is a fallacy that the coronavirus is a leveller, impacting people of all socio-economic backgrounds in equal measure, the former chief executive of Unilever, Paul Polman,has pointed. Many poor people cannot afford to self-isolate, particularly those working in the informal sector.

- Cities, too dumb for pandemics

The design of cities, where 55 per cent of humanity lives, often in close quarters, has exposed their vulnerability to pandemics. “The “unthinkable” must be part of good urban design practice from now on,”

- The best companies are revealing themselves.

Regular outpourings of corporate communications in recent weeks have expressed how much companies “care” and how “committed” they are to help fight the coronavirus. Some have been genuine. Others not. Unlikely partnerships have formed between rivals in a range of industries, from pharmaceuticals to tech, to combat the pandemic, pointing to a future where cross-sector collaboration is more common.

What do you think?