From Microplastic to Nanoplastic

Fragments of plastic smaller than 5 millimeters in length are known as “microplastics,”

The scientists have started to refer to even more microscopic fragments—generally smaller than 1,000 nanometers—as “nanoplastics.”

In a 2019 report, the World Health Organization found that we’ve unknowingly ingested microplastics for decades without clear negative consequences, saying that research into potential health effects is needed. While there’s much we don’t yet know, we have learned that micro- and nanoplastics are everywhere. Snow in the Arctic carries substantial amounts of microplastic, according to a 2019 study in the journal Science Advances, and even more has been detected in the Alps. Microplastics can even be found in the seemingly pristine sand of Hawaiian beaches.

Given this, researchers are concerned that these plastics can make their way into the tissues of our bodies, according to Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., the recently retired director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Toxicology Program. “Nanoplastics can easily cross all kinds of barriers, whether it’s the blood-brain barrier or the placental barrier, and get into our tissues,” Birnbaum has said. Breathing in nanoplastics might introduce them into our cardiovascular system and bloodstream, for example.

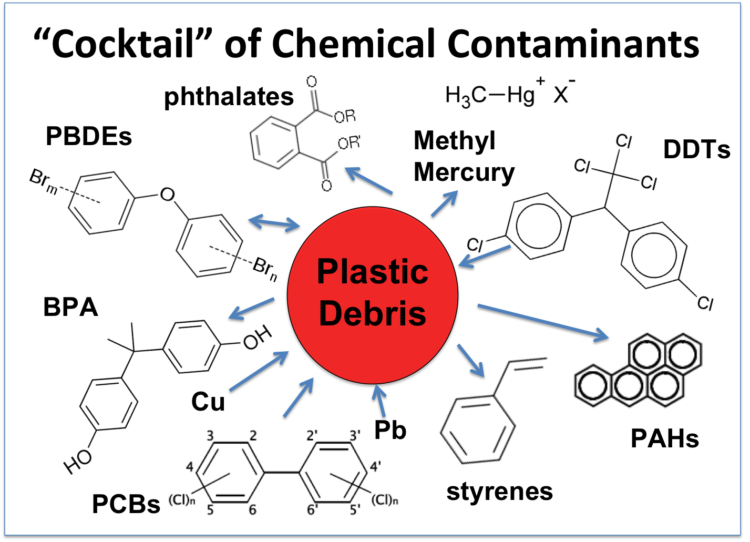

It’s also possible that nanoplastic particles might create a systemic inflammatory response, according to Phoebe Stapleton, Ph.D., an assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. Her research has previously shown that inhaled metal particles can harm the cardiovascular health of a developing fetus. And her animal research has also confirmed that when a mother breathes in nanoplastics, the particles can be found in many places inside the fetus. “We know that after exposure, the plastic particles are everywhere we look,” Stapleton says. “We don’t know yet what those particles are doing once they’re deposited there.” Other researchers, like Myers at Environmental Health Sciences, are concerned that nanoplastics could possibly release harmful chemicals (such as BPA) into our bodies.

Another area of inquiry focuses on the fact that microplastics act like magnets for additional toxins, picking up pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), chemicals now banned from manufacture in the U.S. but still present in the environment. According to Linda Birnbaum, formerly at the NIEHS, if we later ingest or inhale contaminated microplastics, they may release these substances they’ve picked up into our blood or organs, along with whatever chemicals are also in the plastic itself.

What do you think?